Among the many things I severely dislike about JavaScript is working with applications that have oodles of global variables, multiple .js libraries and dozens of loosely organized, individual functions. This is a very common pattern (or perhaps an anti-pattern). But it’s a terrible way to code for medium to large projects, especially where you have to share your code. Here’s a highly simplified example:

var someNumber = 2; //Global variable

function add(number){

return someNumber + number;

};

alert(add(4)); //displays "6"

It’s unfortunate that this pattern is reinforced in authoritative books, blogs and articles. It’s completely pervasive in the majority of examples you see on the web. The downside is modifying, testing and troubleshooting this pattern can be an absolute nightmare. I compare it to building a fragile, multi-level house of cards: one wrong bump and it all falls down.

There is a better way!

So, I offer an easy-to-implement solution: where possible place your functions and properties in Class-like objects and all will be so much better. It’s not quite what you get with strongly-typed object oriented languages like C# or Java, but it works. Besides, if you use this pattern in your project then cats and dogs will live peacefully side-by-side and the universe will be in balance. The best news: this works perfectly fine with plain old JavaScript (POJO). And, if you are using something like jQuery use can use some version of Classes with those too, and I highly recommend it.

Here’s the fundamental pattern of a JavaScript Class:

function Add(){};

var someMath = new Add();

That’s very easy…right?? The advantages are many and include the following:

- You get a powerful framework for logically grouping functionality. This lends to scalability and ultimately stability in your projects.

- You can easily extend this pattern using prototypal inheritance.

- You can take advantage of encapsulation.

- You can implement inheritance and polymorphism.

POJO Class Pattern using Object Namespaces

Here’s an expanded example of the pattern with two levels of namespace separation using a standard Object :

if (!com) var com = {}; //1st level namespace

if (!com.ag) com.ag = {}; //2nd level namespace

if (!com.ag.Add) {

com.ag.Add = function (value) {

/// <summary>Demonstrates the plain old JavaScript pattern for classes.</summary>

/// <param name="value" type="Number">Any number.</param>

this.getValue = function () {

/// <summary>Returns the property passed to the constructor.</summary>

/// <returns type="Number">A number that was passed to the constructor.</returns>

return value;

},

this.add = function (number) {

/// <summary>This method adds value property + number</summary>

/// <param name="number" type="Number">The number we want to add.</param>

/// <returns type="Number">The number passed to the contructor plus this number</returns>

return value + number;

}

//For Visual Studio intellisense cues

com.__namespace = true;

com.ag.__namespace = true;

com.ag.Add.__class = true;

}

}

And, here’s how to use this class:

var test = new com.ag.Add(2); alert(test.add(4)); //displays "6"

POJO Class Pattern using window[] Namespaces

Here is a slightly different version of the pattern that uses the window object, the results are the same:

if (!window["NS"]) window["NS"] = {};

window["NS"].Add = function (value) {

/// <summary>This class uses addition</summary>

/// <param name="value" type="Number">The number we pass to the contructor.</param>

this.getValue = function () {

/// <summary>Returns the private property called value.</summary>

/// <returns type="Number">The number passed to the contructor.</returns>

return value;

},

this.add = function (number) {

/// <summary>This method adds value + number</summary>

/// <param name="number" type="Number">The value we want to add.</param>

/// <returns type="Number">The number passed to the contructor plus this number</returns>

return value + number;

}

//For Visual Studio intellisense cues

window["NS"].__namespace = true;

window["NS"].Add.__class = true;

}

Here’s an example of how to use this class:

var test = new NS.Add(2); alert(test.add(4)); //displays "6"

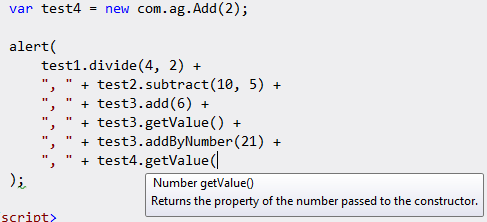

You are probably wondering about the funky xml comments. That’s for Visual Studio 2010’s built-in intellisense. I think but I’m not 100% certain that these work with Visual Studio Express as well. If you know for sure then please drop a comment. Notepad++ and other tools are okay for small projects but you can thank me later when you use this Class pattern along with built-in intellisense for any project that involves more than a dozen or so functions. And that’s not all – you can also see intellisense across different .js libraries. It’s all about productivity and ease-of-debugging. And, everyone will thank you when they have to re-use your code.

I’ve also attached a screenshot below to show you what the Visual Studio intellisense looks like. Also note in this example, the physical file, Add.js, in in the directory /scripts/com/ag/Add.js and I’m writing code in index.html which is at the root directory. How cool is that?!

References

Sample application that demonstrates the Class concepts

Douglas Crockford’s [awesome] JavaScript Blog

Visual Studio JavaScript Intellisense Revisited

Creating Advanced [JavaScript] Web Applications with Object Oriented Techniques

Object Oriented Programming in JavaScript

Write Object Oriented JavaScript Part 1

The Format for JavaScript Doc Comments (Visual Studio)