If you are a developer building applications that require location information then you need to know what is really possible with the HTML5 Geolocation API and not a bunch of hype. The blog post attempts to give you some insight into how it works with desktop and mobile browsers as well as having a greater appreciation for what is and what isn’t possible. I’m going to show you that accuracy depends on many factors, some of which are beyond your control, and at best the location information returned by the API is just an approximation.

[Editors note: as of June 29th, 2013 Part 2 of this post is now available]

Most common use case. For the most part, HTML5 Geolocation works just fine in dense urban areas when you are stationary with your laptop or smartphone Wifi turned on. This is the use case most commonly cited when questions are asked about accuracy. This makes sense because urban areas have many public and private Wifi routers and cell phone towers are typically closer together. As you’ll see, HTML5 uses these and other methods to pinpoint your location. However, it’s not always that simple and below are some other use cases that you should take into consideration.

How does the API work? Depending on which browser you are using, the HTML5 Geolocation API approximates location based on a number of factors including your public IP address, cell tower IDs, GPS information, a list of Wifi access points, signal strengths and MAC IDs (Wifi and/or Bluetooth). It then passes that information to a Location Service usually via an HTTPS request which attempts to correlate your location from a variety of databases that include Wifi access point locations both public and private, as well as Cell Tower and IP address locations. An approximate location is then returned to your code via a JavaScript callback.

As an example to show you what type of information is sent to a Location Service, I did some basic testing with Firefox 11. Firefox uses Google’s Location Service. On a related note, as far as I can tell with Firefox 11 it isn’t passing cookies any more where in Firefox 3.6 they use to pass a user ID token.

Firefox 11 browser sends queries to https://maps.googleapis.com/maps/api/browserlocation/json? The example results have been obfuscated, but by looking at it you should get the idea of what content is being sent:

GET /maps/api/browserlocation/json?browser=firefox&sensor=true&wifi=mac:01-24-7c-bc-51-46%7Cssid:3x2x%7Css:-37&wifi=mac:09-86-3b-31-97-b2%7Cssid:belkin.7b2%7Css:-47&wifi=mac:28-cf-da-ba-be-13%7Cssid:HERESIARCH%20NETWORK%7Css:-49&wifi=mac:2b-cf-da-ba-be-10%7Cssid: ARCH%20GUESTS%7Css:-52&wifi=mac:08-56-3b-2b-e1-a8%7Cssid:belkin.1a8%7Css:-59&wifi=mac:02-1e-64-fd-df-67%7Cssid:Brown%20Cow%7Css:-59&wifi=mac:2a-cf-df-ba-be-10%7Cssid: ARCH%20GUESTS%7Css:-59 HTTP/1.1

Which location service do browsers use?

Not all Geolocation services are the same, and they certainly don’t all use the same algorithms and exact same databases. Because of this the results typically vary across browsers that use different Geolocation services.

Here’s my best attempt to document which Geolocation service each of the major browsers are using. I haven’t done any definitive testing however I do know from experience that different browsers and even different laptops for smartphones will return different locations when tested from the exact same location. Some location services are better in some cities and others are better in other cities. I haven’t come across a definitive list, most likely because the information is constantly being updated. I’ve included a link to a demo application at the bottom of this blog where I encourage you to also test the API against different browsers.

- Chrome uses Google Location Services.

- Firefox on Windows uses Google Location Services.

- Firefox on Linux uses GPSD – https://catb.org/gpsd/. I’m not sure if this includes Android. I haven’t had a chance to test it yet.

- Internet Explorer 9+ uses the Microsoft Location Service.

- Safari on iOS uses Apple Location Services for iPhone OS 3.2+.

- I’m not sure what Safari on Windows uses. With all the public distrust between Apple and Google, I wouldn’t be surprised if Safari on Windows also uses Apple’s Location Service, but I haven’t found any documentation to verify this and I haven’t tested it.

- Opera uses Google Location Services. On a related note, I’ve also noticed that mobile Opera on Android accesses the GPS. This is something to consider from a battery usage standpoint.

Not all browsers support HTML5. It’s important to note that not all browsers support the HTML5 Geolocation API, for example Internet Explorer 8. The HTML5 Geolocation API is built into the browser and is accessible using JavaScript methods that access the navigator object. In order to work it requires HTML5 support in the browser. You can research whether or not a particular browser supports Geolocation by going here: https://mobilehtml5.org/ or https://caniuse.com.

Additionally, if a user has disabled JavaScript for some reason, then your Geolocation app won’t work in their browser. JavaScript code is required to access the API.

HTML5 Geolocation requires an internet connection. If you lose your internet connection then you won’t be able to access the Location Service. With no internet connection most browsers will not return a location. Sometimes you can access a cached location that is stored in the browser by the API. But, that cached location is the last valid location that was calculated by the API.

Is Wifi turned on or off? If Wifi is turned off on your phone, desktop machine, laptop or tablet , the Geolocation API service will try to find your location by other methods which include your public IP address, Cell tower ID triangulation or GPS. Public IP addresses databases usually return a location for your internet providers Point of Presence or PoP. Furthermore, some internet provides offer rotating IP addresses. So you get to use one IP address for a particular time period such as 48 hours and then you get a different one. So a Public IP address is usually only good enough to locate you to a particular City, or a general area of the City, or a Country depending on where you are in the world.

As for Cell Tower IDs it depends on what type of information your particular phone and Telco Carrier provides to the API. Some smartphones only return information on the current tower that the phone is pinging, which obviously makes triangulation very difficult and decreases accuracy to within a radius around that tower.

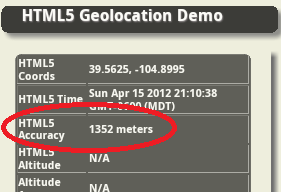

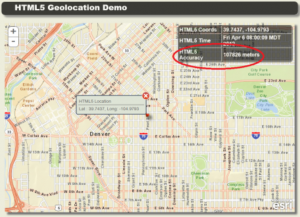

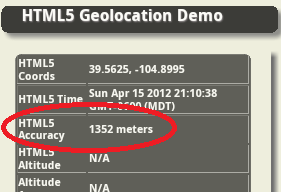

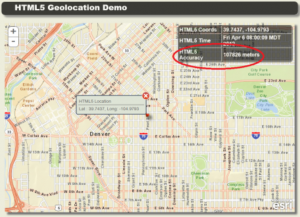

I’ve noticed that the native Android browser is significantly less accurate without Wifi. Without it I typically see accuracy numbers in the 1000+ meters range. As soon as I turn Wifi back on and I’m in a neighborhood or downtown area, the accuracy drops to less than 75 meters almost instantly.

Are they in a rural or urban location? Granted the vast majority of users will be in urban locations. However if you have requirements for users traveling outside of urban areas then this section applies to you. Geolocation in rural areas is significantly less reliable. If Wifi is turned on but the user is not near any Wifi access points, then the Geolocation service will also attempt to fallback to the other methods mentioned above. Triangulation can be much more difficult in rural areas where towers are spread further apart, and for browsers that don’t use GPS the accuracy will suffer significantly.

Are you moving or stationary? Being stationary in an urban area offers far better accuracy with the Geolocation API than when you are moving. On my native Android phones it’s rare to get an accurate reading while driving around town. Occasionally a sporadic result would be returned when you stop at a light. To date, I have never gotten a valid reading while driving on a highway at speeds over 50 mph.

Is a VPN turned on? If a VPN is turned on, then the location will resolve to the VPN’s public IP address. For example, a user in Denver is logged into the company VPN which host is hosted at their headquarters office in a suburb of Dallas, Texas. The HTML5 Geolocation API will resolve the location to the headquarters public IP address in Dallas and not the user’s actual location. Quite a few corporate users have VPNs for security reasons.

Custom Geolocation as a fallback? Depending on your requirements you may want to implement your own IP Geolocation using a company such as IP2Location. Or use a third-party Geolocation service, such as Skyhook, as a fallback. Remember IP Geolocation only returns locations to a City or an area within a City. So, if you need more accuracy than that for your application, then don’t bother with this approach.

The downside to custom IP Geolocation is that this requires writing a server-side service to grab the browsers IP address. All server-side languages such as PHP, C#.NET, Java and JSP support these capabilities. You also have to subscribe to another service that lets you query their database by IP address and get a return value of an approximate location. There is no current way to get this information from the browser, on the client-side, using JavaScript.

HTML5 Geolocation doesn’t meet my requirements, what do I do? If you have critical requirements for gathering more precise location information than the HTML5 Geolocation API is capable of delivering then I’d recommend building your application using a native API such as Android or iOS.

How can I test this? You can test HTML5 Geolocation in different browsers using a test application that I built. I recommend trying it on different browsers and comparing the results yourself:

https://andygup.net/samples/html5geo/

References

Mozilla FAQ

Mozilla Developer Network

Google Location Service

W3C Geolocation API in IE 9

Safari Developer Library

Opera Geolocation

IP Geolocation

W3C – Privacy of Geolocation Implementations

Apple Q&A on Location Data